A Tale of Transformation by Mother Wild: The Second Lesson Impassions

Feminine Wisdom, Way-finding, Patriarchy, Service

Hello, again, dear readers. I normally write monthly, but in the interest of keeping the thread of this story alive, I don’t think it would be a good idea to put a month between installments. Therefore, though the pace is, for me, relentless, I am soldiering on. This installment is longer than those to come, having three parts instead of two.

For those of you who would like to catch up, there are two previous installations, A Cautionary Tale by Mother Wild (my original working title, sent out as a teaser but is actually necessary to read as an introduction) and A Tale of Transformation by Mother Wild: The First Lesson Alarms.

And by all means, please comment. Fiction (however collaborative it might be) is new for me. How is it landing for you?

The Second Lesson Impassions

Part 1: In Which The Source of the Calamity is Revealed

Arriving back in Laforey, accompanied by the food and medicine, I promptly began my inquiries. Most were still too sick to be queried. However, some of the first to succumb were beginning to recover. I was able to arrange an interview with a nearby couple, the husband of which was known to me by his work as a servant for the ruling council.

The walk was short, but the mood was dismal. Emaciated dogs lay flat as rugs as I passed, only some managing to lift their heads. Without even enough energy to growl, they listlessly dropped their chins to the ground, eyes lethargically following my path. “Were their owners too sick to feed them?” I wondered anxiously. “Were their owners even alive?”

After knocking on the door of a neat, little row house, my patience was rewarded by the sound of slow, heavy footsteps approaching the door. “Tollas,” I hypothesized. Upon opening the door, he followed it backwards, placing a few feet of distance between us while his wife slowly approached from behind. Both were gaunt, with dark circles under their eyes causing them to appear ten years older than they were. “Let us receive you on the porch,” Tollas, offered. Turning, I noticed that one of the three chairs, set carefully on the porch, was as far distant from the others as the space would allow.

“Thank you for your thoughtfulness. And for agreeing to meet with me. I hope it is not too fatiguing at a time like this!’

“Oh no!” spoke up the wife, “it is very important that we discover the cause of this terrible disease so we can prevent it in the future! But thank you for your concern.”

Once seated, I opened the inquiry. “Have you any idea how you might have become exposed?” While they couldn’t say definitively, they noted that the day before the illness struck they had taken, to supplement their evening meal, some preserved foods from Tarnello.

“How did you happen to come upon food from Tarnello?” I asked, puzzled.

“My brother was one of the first to leave as well as one of the first to return,” said Tollas. “Though he was quite sick by the time he arrived, he sent us some food by way of his daughter—before she got ill.”

His response only served to raise more questions. I was now positively perplexed. “One of the first to leave? For where?”

“Have you not heard about Tarnello’s betrayal?” The man asked, incredulously.

“No! I’ve been away in … “ I started to answer, but considering where I’d been, resolved to omit that detail. My mind, however, became fixed on a disquieting question: Had I been duped by the Tarnellons in some way?

“I’ve been out of the country.” I explained, “which, I suppose, prevented me from succumbing to the illness as well. There’s been no one at hand to enlighten me since my return, just a couple of days ago. Please tell me!” I entreated anxiously,. “What terrible thing has Tarnello done!?”

The couple looked at one another as if they weren’t sure how to begin. Then the woman began to speak. “We really only know part of the story,” she said, “We were the ones who stayed behind. You see, a group of Tarnellons had come through town, spreading glad tidings of a bounty of food from their latest harvest—much more, in fact, than they ever could eat. Not wishing it to go to waste, they’d formed the idea of preserving and offering it to us, with the notion that our farmers could put aside their spades this spring. Their labor would not be needed. The Tarnellons could feed us all. For this they asked only that we come and collect the food.

A few of the farmers enthusiastically received the idea and left post haste, leaving their fields fallow in their eagerness for a year without labor. Soon other friends and neighbors joined the caravan as well until, finally, the great majority of Laforeyan men were crowding the road to Tarnello, each one eager to reap the benefits of Tarnello’s great good fortune!” Here, she stopped, as if all had been explained.

“And so?” I prompted, “was there a problem? Where is the betrayal?” Tollas’ wife, tired now from speaking, entreated her husband to carry on the tale.

“There was, without doubt, trickery afoot,” he declared. “To begin with, the “vast supply” of food, promised to last a year, was in truth so meager that to share with families at home—like us—was to guarantee a famine. Secondly, we suspect it was the food itself that sickened us. Though we enjoyed its fine lavors, we were both markedly ill by the following morning. After three successive days of purging gripe, we thought to send a message to my brother’s house. However, we could find no one to take it. Slowly, we realized that the street had grown increasingly quiet since our first day of sickness. We no longer heard the sounds of carts on the road, children playing in the distance, doors slamming or cheerful conversation among passers-by. Not even a barking dog. Nothing but the birds. After much puzzlement, we concluded that all were sickened just as we were.”

“What a terrible misfortune!” I exclaimed. “But it’s hard to believe it was intentional. Couldn’t there simply have been some mistake in the preserving process!”

“Well, that was our guess as well. However, those who left did not return for a very long time, and what was worse, no one could locate them. Several family members rode to Tarnello looking for their loved ones, but no one knew anything about them. Finally, a month or so later, the first travellers began straggling back—with hardly any food and terrible stories of betrayal.”

Well rested, now, his wife spoke up again. “Most of my other family members stayed home like we did. After a few days my sister began stopping by every day to check on us. She insisted that we open a window so she could speak to us from outside. In fact, she checked and reported on all of us. Some grew ill and some did not. It was the ones who ate the food who got sick. From her I learned that my own father, on impulse, accompanied a friend of his to Tarnello to help with the haul. He’s only just returned home—at last! Of course he did fall ill but is now somewhat better. He has told my sister, with great gravity, a few terrible tales about his trip to Tarnello. She shared them with me.

I dare not repeat them. He is unable to share many details as he is still too weak to speak over much. But I can give you directions to the homes of some who’ve returned and are starting to mend. They were lucky to get out alive, in my opinion,” she added darkly.

“Oh, that would be wonderful!” I exclaimed. “I thank you both very much for your assistance and for expending your scarce energy to share your story with me today.” After taking down the addresses I insisted they go inside and rest. “I hope the herbs are doing you some good.”

“Oh, they are, they are!” the wife assured him. “Instead of getting worse every day, we are now getting better. We understand that you are the one responsible for obtaining them. Thank you so much. You are the people’s savior!”

Laughing at her—and at myself for loving the sound of that phrase—I took my leave. Soon I had made arrangements to meet one of the travelers. Since he was a tutor by trade, I hoped he’d interview well.

Image Credits (elder woman): Carl Heuser, (canned goods): Freerange, Jarmaluk

The Second Lesson Impassions

Part 2: In Which Betrayal is Revealed

Following the directions I’d been given, I wended my way to a tidy little home in a residential part of town where the trade and craftsmen lived. All along the way, though, I spied signs of sickness and neglect. Full and malodorous chamber pots sat outside some houses, where their users hadn’t the energy or will to empty and clean them. Flower gardens had sprouted any number of weeds. Berry bushes had obviously been robbed by birds, leaving seeds and mangled fruit behind. And for the first time I saw emaciated corpses, thrown out of dwellings and into the streets. In one disturbing instance, I heard squabbling in a lane perpendicular to me. Turning to investigate, I beheld a bevy of ravenous dogs fighting over what appeared to be a human body—no doubt dragged to that location by one of them in hope of a solitary meal. His privacy interrupted, he was in no mood to share.

At last, however, I found the tutor’s home. The door was timidly opened by his young wife, though she, also, looked frail beyond her years. She did not invite me in, nor did I wish her to. Gesturing to a dying garden beside the house which featured a weathered table and some chairs, she suggested we meet there. I was more than happy to oblige. She then left me to fetch her husband. “But sit down!” she entreated me. “We will join you there.” In due course I observed their approach—he, leaning heavily upon his wife as they slowly and painfully made their way to the table. Standing for a moment, he appraised the chair, planning his approach. Then, with a great deal of caution and the assistance of his wife, managed to lower himself into it, grimacing with pain.

“I’m so sorry to have intruded upon you in this way!” I interjected, horrified by his condition.

“Do not be!” the tutor reassured me, his voice surprisingly strong. “It is very important that I tell you my tale.”

“May I bring you anything?” I queried, uncomfortably, “Is there water nearby for you to drink?”

“I will ask, if there is anything I need,” the tutor promised, eager to begin.

“Before I begin, it would be of great benefit to me if you would assist me by sharing with me what you already know.”

Happy to help in that—or any—way, I recounted what I had learned from Tollas and his wife. “Are you, indeed, one who made the journey to Tarnello? And do you, then, have first hand experience with a Tarnellan betrayal of some sort?”

“Yes, that was very helpful,” the tutor replied. “That is where I will begin.

First, you must know that we had been instructed to report to Harberin, a town on the edge of civilized Tarnello—if there is such a thing,” he added contemptuously. “There were many score of us—perhaps many hundred—arriving in a constant flow from the west. We were guided to a dusty field at the end of the town where we were told to leave behind our horses and carts. Wagons of every kind had been assembled and we were told they would carry us to the excess stores. It seemed nonsensical as we could certainly have carried more had we brought our carts, but lacking sufficient information to argue, we followed their instructions good-naturedly enough—tying our horses with the reassurance that they would be tended and finding a place in one of the wagons. It seemed things were fairly organized. But bumping along in our wagon through the barren land, what was left of the day soon turned to dusk and we still had not reached the fabled excess stores. Most of us had eaten along the way and were eying what remained of our food—intended, of course, for the journey home. We’d expected to be well on our way back by then. But those who enquired about the remaining distance were given gruff and cursory answers.

The drivers were all well-armed—each accompanied by an equally-armed second—and sat sullenly with their backs to us for the entirety of the drive. The land surrounding us grew more and more inhospitable—rocky, dusty, gray. By the time darkness descended, I was fairly confident that we were in trouble—as, I think, everyone else was too. The chatter died down and a certain grimness set in. Still, the wagons traveled on. We were crammed into them as tight as could be, which perhaps made it a little easier for me to close my eyes and drift off for periods of time. Suddenly, in the middle of the dark, moonless wasteland, we came to a halt. The drivers pointed to a low ridge of dirt in the distance where we could relieve ourselves. Not having been allowed the opportunity for the duration of the ride, we all shuffled gratefully in that direction. There we found a newly dug latrine. It all seemed inexplicable.

We were then guided to a crude, outdoor pavilion where we were served a grainy gruel of some sort and some foul-smelling water. Most of us chose to eat our own food, which mysteriously angered a few of the drivers. “Enjoy it while you can!” they glowered menacingly. Setting themselves as guards on the perimeter of the pavilion, they gave us no further instruction until the sun began to rise.

Just as the surrounding structures began revealing themselves in the growing light, a carriage came swiftly toward us from the road. From it emerged several more men, all armed with various forms of weapons. One, who was apparently the leader, began barking orders. “Line up two by two!” he commanded. Groggily we arose from the hard wooden tables we’d been sitting or sleeping on for the past few hours. “Make haste, you butt-dragging, swine!” he shouted angrily. Our handlers descended upon us, poking at us in our confusion, with the blunt ends of their knives and short-swords in an effort to herd us into place. At last they were satisfied. “Now march!” commanded our overlord. Approaching the outbuildings, we seemed to be headed toward a wooden framework protruding from the hills surrounding us. Toward the back of the line, I followed the others, until at last it was my turn to stoop through the entrance to the chilly, dark passageway within. It wasn’t a cave, I realized, studying the walls as the light grew dimmer. It was a mine!”

Slowly making our way forward in the cold, damp, darkness we eventually arrived at a large, dimly lit cavern where we were issued the barest necessities needed for mining. From the central cavern, many shafts could be seen, branching out in every direction. We were each directed to one or another. Thus began our first day of mining for gold.

I will not, at this time, describe a great many of the details, as I fear I’d come to the end of my strength before completing my story. Suffice it to say that I was imprisoned there for nearly a month. They brought us out into the dark night at the end of each working day and fed us their finest gruel. They gave us nothing warm to wear—either in the chilly, dark tunnels of the mine or the cold, windy nights in the outdoor pavilion. As one might expect, the oil-wicked lamps they fastened to bands around our heads were exceedingly dangerous. Many were injured or died due to the harsh conditions and complete disregard for our safety.

When we became too weak and exhausted to work, they were compelled to let us go. The only assurance that they ever gave us was that we would, indeed, be paid—in the very gold we were betrayed into mining. When, after what seemed like an eternity, I and a few others were deemed too useless to continue, they threw us to the ground outside the mine entrance, then tossed a few gold coins in our direction. Turning their backs they re-entered the mine and were quickly erased by the darkness. I only wish my many wounds and memories could be erased so easily,” he added bitterly.

“Even after gathering every coin that we could find, there was only a small handful for each of us. Knowing nothing of gold, I had no idea whether this made me a rich man or a pauper. While we were wondering what to do, some of the same wagons that had delivered us arrived with our replacements. For one of our precious gold coins, we were offered a ride back to Harberin, where we’d trustingly left our horses and carts nearly a month before. Being quite debilitated, we were in no position to argue. Unsurprisingly, we could discover neither horse nor cart at the fence where we had left them. The drivers knew nothing of excess storage but there was a mercantile nearby so they dropped us off there—though how we were to return home nobody knew.

On our approach to the store we spied a field behind it, bursting with carts and buggies. I had a suspicion that mine was somewhere among them. Inside, the store’s supply of preserved foods was quite low. We were told that many seeking the same had arrived before us. Our drivers, however, had led us to believe that we were the first beaten-down miners that they’d driven back to town. The proprietor claimed to know nothing of excess food to be given away. Their food, they assured us, was absolutely NOT free—a ridiculous assertion! We must use our gold coins to buy it. ‘But how will you get it back home?’ they asked with faux innocence—knowing, I suspect, full well our predicament. ‘You can go pick yourself out a cart in the back—for a sum, mind you,’ they offered, as if doing us a favor. It ‘so happened’ that they also knew of a stable on the outskirts of town that had recently acquired many horses. Perhaps we could purchase one there.

Seeing no other option I set out in a misguided attempt to stagger to the stable, but a good villager, passing by in a buggy, offered a ride out of the goodness of his heart. ‘How much?’ I asked him, fearfully eying my last few coins.

‘Good man, you need my help. I am happy to give it to you.’ He assisted me into his buggy, as I tried not to gasp too loudly from the pain. He appeared quite curious about my peculiar disabilities but I was in no mood for talking. Once at the stables, he lowered me gingerly to the ground, touched his hat and proceeded on his way. Thankfully, not all Tarnellons are detestable.

I stood, teetering, for a moment, working to regain my equilibrium. I was about out of energy, never mind gold coins. Entering the dark office, I queried the manager. My own horse, if I could find her, would cost me three coins. My cart had already cost two!”

Here the tutor’s slowly fading voice, gave out at last. “My dear, you know the story. Would you kindly finish it for me?” he rasped.

In urgent haste I jumped to my feet! “Good woman, where is the water? Let me bring some to him!” I begged her desperately, as if water alone was all that he needed. He took some, however, which helped somewhat, but clearly he needed his bed as well. His wife and I, working together, helped him out of the chair and from there to the steps in front of the door. Grabbing a railing, there, he dismissed my further assistance. As they passed through the doorway, his wife turned back to request that I wait for her. I settled myself in the tangled, brown garden once again, pondering all that I’d heard thus far. It was too much to fathom. What evil scheme were the Tarnellons up to?

The tutor’s good wife returned in good time, considering her own poor condition. She eagerly continued on with the tale before even taking her seat—either to oblige me or more quickly to return to her husband. I wasn’t sure which.

“Luckily, most good men love their horses so they’d recovered their own, leaving our Sharling for Jor to find,” she began, referring to her husband. “He saw her in the corner of a stall crowded with three other horses. There were no stable hands to be found and the stall hadn’t been cleaned in quite some time. The stables’ sudden “acquisition of horses” must have overwhelmed the help. Our Sharling was hungry, thirsty, and filthy, but Jor said that her joy upon spotting him brought him back to life. I wish I could have seen their reunion. He found food and water for her, and tools for grooming. Others, however, had upgraded their saddle and tack by helping themselves to Sharling’s instead so Jor found an old saddle and rooted about in the stables until he’d gathered everything he needed. He said he climbed onto Sharling’s back and rode straightaway out of the stables before anyone could arrive to demand more payment.

The gold he had left bought only enough preserved food to cover the bottom of the cart—not nearly enough to last a year, even if it were only for him, but of course the dear man needs to feed me as well. Thank goodness we have no children yet! Making himself as comfortable as he could (which I’m sure was not very comfortable at all!), he managed to wend his way home. But illness set in on the second day of travel as, having no food, he’d had to open a bottle of Tarnellon food along the way. Of course, he didn’t know that it was the food that had sickened him, so once he got home he gave some to me, as our larder was almost bare. With so many fields unplanted, you see, there’s no food to be had!

Speaking of food, I understand it is due to your diplomacy that we were all given food and medicine. I am very happy for the opportunity to formally thank you. It is so good to be on my feet again. As for my poor husband, well, he says he was fairly well finished before the illness overtook him. He keeps telling me not to expect a happy ending …” Trailing off, his wife began to weep, then to wail, then to sob uncontrollably.

“How frightful!” I cried in alarm. Then, after a moment’s thought, I added, in an attempt to console her, “You never know though, madam, what healing might occur after a long rest, the right medicine, and enough healthy food.

All the same, I must say, I’ve never heard tell of such difficult times. With the information you have given me, I believe we can settle the score. The Tarnellons’ behavior is unconscionable and must be avenged. I am so heavy hearted that I feel I can barely walk back to the ruling council. But they must be told,” I declared, not mentioning the Lovahtians who would certainly receive a report as well.

By the time I arrived at the offices, having re-spun the tutor’s tale over and over along the way, I was livid about the Tarnellons’ betrayal—betrayal not only of the many who were taken in and marked by it, perhaps for life, but betrayal of me as well. I could find no reason not to doubt for one moment that the very men who drank my health and paid for my visit knew exactly what was happening elsewhere in their land—and in mine. This was why they suggested I not wander far. They were right about the sickness I might come across but it wasn’t the sort of sickness I’d envisioned. As if that weren’t enough, some of my own council members had perished as well!

Unfortunately, those council members who were healthy enough to work were too overwhelmed with the overall calamity to spare the time to hear my stories. Besides, they’d heard similar tales from others. They were working night and day to find a way to right a ship that had lost its sails and much of its crew. Knowing their task to be essential, I left them to it … while I set my sights on revenge!

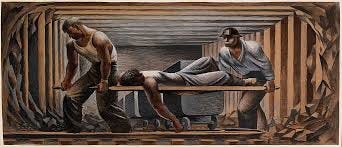

Image Credit (injured miner): Fletcher Martin

The Second Lesson Impassions

Part 3: In Which Madam Majelice Speaks of Passion

It was only a matter of a few days before I was able to return to The Land of Peace, where, at last, I could unburden myself by the telling of my wretched tale. With fair warning about the devastating nature of the story, I passed on the stories I’d been told, my voice often quivering with rage. But when, at last, I had come to its end, still, I went on—ardently cataloguing the atrocities leveled upon us, until, having reached a feverish pitch, I concluded with an impassioned cry for the punishment of Tarnello! Certain that no one could hear the stories without becoming enflamed, I was surprised to find, at the end of my speech, that the room remained silent—for so long, in fact, that I was hardly able to endure it.

I wanted an explosion of outrage.

I wanted a full-throated conviction.

I wanted a war party!

After what seemed an insufferably long time The Patriarch rose to speak. “Ah! This is very troubling. Let us take some time, you and me to discuss this together—to develop a plan of action. Matriarch Lareesie and Madam Majelice, will you please excuse us for the time being? We will summon you at your abode when we are ready.”

During the two days we spent in consultation we walked the grounds often—I, adamantly advocating for war and drawing battle plans in the earth, The Patriarch, resolutely encouraging reason, diplomacy, sanctions. Sometimes whilst I madly scratched maps on the ground he reached out and took my shoulders, turning me toward him in an attempt to break through my blind passion by capturing my gaze. But his tone only impassioned me further. I could hear nothing in it that hinted at outrage or revenge. I hadn’t yet succeeded at piercing the armor of his principles. And so I tried harder.

By the third day we concluded that we had nothing new to offer each other. He suggested, then, that I present my plan to the Matriarchs.

Waiting alone in the council chambers for the matriarchs’ return, I was, for all intents and purposes, pacing the floor. I was shocked to find the The Patriarch unpersuadable. How could I have failed to make my point? The stories were clearly indefensible!

By the time Matriarch and Madam Majelice took their seats and The Patriarch rejoined us, I was fairly bursting with emotional tension—so much so that the two of them glanced apprehensively at one another. Clearly, my mood was palpable.

With a face that betrayed nothing, The Patriarch urged me to proceed, “Secretary Perri, you’ve cleaved, unwavering, to your plan, accepting only minimal input from me. However, there is still a process to be followed. It, in itself, will be your best guide. So let us begin. Go ahead, Mr. Secretary, and tell The Matriarch and Madam what it is you wish to do.”

Consumed, as I was, with the desire to make myself understood this time, I forced myself to remain keenly focused. At the beginning, I rested my eyes on a spot at the back of the room, heedless of either The Matriarchs to my left or The Patriarch on my right. Speaking loudly and, I hoped, powerfully, I held forth at the full extent of my emotions. “The poisoning of our people is an act of war that must be avenged! Even though, at present, we are too sick to fight, punishment of these enemies of our people must be swift and strong.” As I loosened up I brought my full passion to my speech, searching the room with my eyes yet never glancing directly at my audience of three. “We cannot wait until next year—when, thanks to you, we will be well-nourished and strong again! To levy our revenge we must CRUSH THEM AT ONCE!” Here, I paused a moment for effect.

Then, in a quiet, reasonable tone, I continued. “If they would do this to us, there’s no reason to believe they wouldn’t do it to you as well.

Your standing army is long overdue for an actual skirmish to keep them in shape.” Here, a small gasp escaped from one of the Matriarchs. Nevertheless, I pressed on. “Therefore, I present you with the following proposal. I humbly ask that you attack the Tarnellons on our behalf. Not only does this deliver the quickest revenge, but it will also surprise them. They don’t expect such a thing from The Land of Peace. Because of that, you will be able to penetrate them deeply.”

After only a very slight pause to let my point sink in, I went on. “I know this is a great deal to ask.” Now, a respectful pause. “Please keep in mind, however, that the Tarnellons are guilty of heinous crimes! I realize, of course, that we are already in debt to you—a debt it will take us some time to pay. But the beauty of this plan is that your surprise attack will allow you to access their treasury and carry off their gold, which we will gladly let you keep in return for your food, medicine, and protection!” Then, reaching again for the elocutionary peak, I continued, “As you can see, my strategy is masterful. This Plan. Resolves. Everything!” In the silence that followed this final declaration, I could hear my voice still ringing.

Finding the courage to snatch a glance at them, I could see The Matriarchs to my left still staring, stunned and unseeing, in my direction. At last Matriarch Lareesie broke the spell. Rising and addressing us, she looked only at The Patriarch, directly across from her. “We will now retire to discuss this proposal,” she said quietly.

I felt utterly deflated. What did it take to move the hearts of these cold, emotionless people? Were they made of stone? And, more urgently, how would I survive until we reconvened?

Whatever it was that The Matriarchs did in that seclusion in which they dwell, that cowardly secrecy which cannot, apparently, withstand the public gaze, they took their time. A new meeting was not called for another two days. When it commenced, it was Madam Majelice who rose to speak.

“In my understanding—and Matriarch Lareesie has confirmed this,” she began, “—The Land of Peace has no interest in gold coins. As you can see, they do not use them here. Theirs is an entirely different kind of economy, based on sharing and service. The injection of some intermediate currency, gold, for example, between a need and a service was intentionally rejected here—as ‘Currency,’ they say, ‘is the shortest path to hoarding and greed.’ Hoarding and greed by their very nature, they believe, set the stage for scarcity and despair. Wealth, therefore, is a worthless thing. In the lands where it is valued, the people are told it will bring fulfillment. Well, if fulfillment means convenience and comfort for some at the expense of the many, then perhaps its proponents are right. Service and sharing, however, are the most reliable roads to the heart’s fulfillment while at the same time being very difficult to hoard.”

Of course I knew already, as everyone else did, that the Lovahtan economy was not currency-based. Her self-important tone felt like a stone in my boot. But certainly—CERTAINLY!—the gold could be traded for things they DID value. Yet, there she stood, implying, FOR THEM, that they would really walk away from it. How could SHE be allowed to speak for them? Not only was it disrespectful, I found her assumption impossible to believe. At bottom, though, it raised the question: What did two women in seclusion know about the ways of the world?!

As she continued, I watched her intensely—aggressively, even. How had she, a woman—a hag, no less—come to have this control over me? But then the realization penetrated that, astonishingly, in that particular moment she no longer appeared as an old hag. Older than Matriarch Lareesie, of course, but certainly not a hag. Why had I thought that before?

At any rate, whatever she was, she had no place in my life, yet there she was—maddeningly wrong. Who would be first to set the poor woman straight?

“Our own people’s situation, though,” she went on, now throwing me a bone, “is truly catastrophic and its resolution will require careful observation.” OBSERVATION!? I groaned inwardly. I want war and she wants “observation?” We could not be further apart. “Profound questions need to be asked,” she continued. “Our farmers have always viewed their calling as a sacred service to our people. Why did they agree so willingly to this nefarious scheme? Something is missing from this story. Whatever it is, it has quelled their passion for their work. The farmers I knew would never have been deceived this way because they never would have left their farms!

Something else is missing as well—another mystery that lies behind this catastrophe. To find it we will need to look beyond the surface. To what end would the people of Tarnello commit such a heinous act? With one hand, they are lavishly entertaining you. With the other they are enslaving our citizenry. These two things do not fit together. What is the missing piece? THAT is the real problem. Not our so-called enemies.

And speaking of the farmer’s passion,” (oh, when would she sit down?) “what about your own? What fire is alive in your heart? What passion in YOU has not been met that you hearken after the false premise of war? We need some fire, this is true. The fire that drives us to find the solution. But war is almost never that solution and certainly never the first one to reach for! The fine, peaceful Lovahtans have already saved our people’s lives. If they have a passion, it is a passion to serve. We would be asking them, in return, to endanger their lives—and for something they neither need nor want. I cannot go along with that. Please seek other solutions. I will never agree to this one,” she stated, quietly.

Though she never raised her voice, I felt a sting as if slapped in the face. Its sharpness angered me. Instinctually, I advanced a couple of steps toward her—an expression of my animosity. “What right have you to respond this way!?” I demanded. “I am doing the hard work of saving our land! It is not all fun and games! Sometimes there are difficult tasks that must be carried out. Clearly, you women do not understand such things!!”

Even before I had completed my retort I could hear Patriarch Rossmuir’s quiet remonstrances: “Shush! shush!” he interjected after each harsh ejaculation—like a nursewife hushing her crying baby. When it was clear I was finished, he rose to speak. “Secretary Perri, you do not show an understanding of the balance between The Matriarch and The Patriarch. The Matriarch has complete power to accept or reject our proposals. This balance is at the heart of our peace. And our peace is at the heart of our success. You came here to find out what made us successful. If you cannot submit yourself to this balance, you have no chance of bringing your own land to peace. You may become great warriors. Your land may grow rich with the spoils of war. But you will never be peaceful. Unless peace is your goal, you should return home at once. It would go better for you, however, if you were to stay and let this process do its work on you. You will emerge a better leader. You can trust me on this.”

I did not agree. I was angry and felt publicly shamed—by a woman, no less! I wanted to prove them all wrong. Rather than satisfy them with a response, I strode angrily from the chamber. On the way to my lodgings, however, a singular event occurred. Lost in my dark and disturbing thoughts, my walk was strangely disrupted by a crow with whom I almost collided. Recoiling and waving my arms to bat it away, I realized that its interference had been intentional. Seeming to stop at eye level, just outside my reach, it stared intently at me, then flew away. But somehow it managed to break the spell.

Feeling my anger draining away, I completed my walk. Surprisingly, though, just before reaching my rooms, I found myself heading back to the council chamber. Since I was almost sure to be proven correct in the end, I reasoned, I wanted to continue the process. In addition, I had a great fondness for The Patriarch and felt pride in our friendship. Rather than leave, as if I hadn’t the courage to finish, I preferred to stay and be exonerated. I knew, now, what I had to do and was eager to get started with it.

Outside the chambers, I saw Matriarch Lareesie and Madam Majelice in deep conversation on a bench. Patriarch Rossmuir himself, I spied wandering among his roses. Seeing me approaching the council chamber they bestirred themselves to follow. When all of us were gathered once again I, somewhat sulkily and without preamble, agreed to remain in the process. The council was summarily adjourned.

Lying in my chambers in Lovahto that night, the storm of passion behind me, I found, in the stillness, that something was yet troubling me. I cast my mind about for clues. No, it wasn’t being bereft of the spell that Anazeh seemed to cast over me in those halcyon days in Tarnello, though memories of our time together often flitted through my mind when it wasn’t otherwise occupied. So completely had I been consumed by catastrophe, of late, that my mind had known no rest. In the calm of the moment I reflected on the wisdom she displayed in countless ways—some of which I immediately recognized, some of which I came to understand over time, and some of which, I’m sure, I have not yet realized. Now, it seemed, a particular one of the many extraordinary ideas she’d expressed was struggling to be remembered. Though my mind had been stirred, her wisdom remained just beyond reach.

If you can!

Oh, you teaser! 😜🙏😎♥️ Maybe I should wait till the story is done so my own passions for more don't bother me. 😄😘

Love it.